|

QUEENSLAND FOREST HISTORY

STORIES

An

alien workforce

Board

introduces a century of forestry

Environmental

system to world standard

Forest

conservation started in the 19th century

A

forestry snapshot

Visionary

changes forestry forever

Motor

vehicles make easy access to natural areas

National

parks grew from bush exploration

Queensland

celebrates 100 years of forestry

Service

celebrates 25 years

Women

of the woods

AN

ALIEN WORKFORCE

by John Schiavo

Forestry's "reservoir of labour"

Former

unemployed men work burnt scrub to plant forests during the Great

Depression

A safe haven for

displaced persons. These temporary forestry camps in rural Queensland were

spartan, but were a "million miles" from war-ravished Europe during and

after the Second World War

One of the most interesting

periods in the history of Queensland Forestry occurred in the years during

and after the Second World War.

With all Australia involved

in the war effort, the construction of defence installations placed a

heavy burden on timber supplies. Forestry was regarded as an essential

industry and measures were taken to ensure that timber was made available

for the war effort.

As the male labour force shrunk, European

prisoners of war were used to harvest Queensland's timber. Prisoners of

war were sent to the Mary Valley as well as the Brigalow district around

Chinchilla.

The need for timber became even greater for

reconstruction after the war. Housing shortages placed a huge demand on

wood supplies but the workforce to cut the timber was not

available.

The solution came in the form of European refugees,

officially referred to at the time as displaced persons. The Australian

Government agreed to accept these people in July 1947.

While

millions of war refugees were resettled in the intervening period, about

one million refused to return to their homelands. The majority of these

displaced persons came from eastern Europe and remained in holding camps

in central Europe after the war.

There were, however, a number of

conditions placed on the agreement between the Australian government and

the United Nations who coordinated the Displaced Persons Mass Resettlement

Scheme.

People entering Australia had to agree to work for two

years in any employment as directed by the Commonwealth Government.

Essential industries in Queensland included the sugar industry and

forestry. After this two-year contract expired, displaced persons were

allowed to find their own employment. The scheme operated between 1947 and

1952.

During this time, between 6000 and 8000 men and women were

employed in Queensland. About 1000 were employed by the Department of

Forestry.

This workforce peaked during 1950 when more than

650 men were employed, primarily in the massive reafforestation program

undertaken by the department.

The largest concentrations of

forestry-employed displaced persons were at Imbil, Amamoor, Widgee,

Gallangowan, Yarraman, Benarkin, Blackbutt, Colinton, Chinchilla, Elgin

Vale, Atherton, and Beerburrum.

While some workers objected to the

remoteness of the work and gravitated to coastal towns and cities, others

remained employed by the Forestry Department after their contract had

expired.

BOARD INTRODUCES A CENTURY

OF FORESTRY

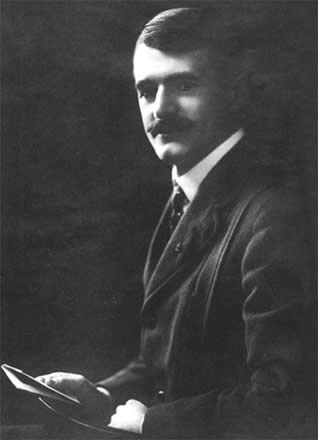

George Leonard

Board

This year commemorates 100 years

since the appointment of George Leonard Board as Queensland's first

Inspector of Forests.

When Leonard Board took up his appointment on

1 August 1900 he began an era of official forest stewardship for the

state.

He was the first of a line of forestry heads who

progressively refined forest management to a science that balanced

ecological needs with community needs for timber, recreation and multiple

uses such as grazing and bee-keeping.

When Board was appointed,

Forestry was a branch of the then Department of Public Lands.

His

staff consisted of two forest rangers, and, for the annual salary of £500,

he administered a rapidly growing industry throughout the

state.

The Maryborough Chronicle in 1900 said of Leonard Board's

appointment: "He is without a doubt one of the most experienced and

capable men in the Lands Department, and he will not only fill the

Inspectorship with credit (he will) make it a most serviceable and

important office."

From a branch in the Public Lands Department,

Forestry became variously the Department of Forestry, the Queensland

Forest Service, and a business group within the Department of Primary

Industries.

While the one-time Forestry Department had

responsibility for almost all forest-related activities in Queensland

(including national parks), forestry administration is now spread across

several departments including the Department of State Development, the

Department of Natural Resources, the Environmental Protection Agency, and

the Department of Primary Industries.

DPI Forestry is the

commercial arm of the Queensland Government's forest production

activity.

The history of the state's forest leaders shows similar

changes.

Leonard Board was an Inspector of Forests. Immediate

successors were known as Directors. Then came Conservators, and now,

Executive-Directors.

Leonard Board served from 1900 to

1905.

Then came P. MacMahon (1905-1910), N.W. Jolly (1911-1918),

E.H.F. Swain (1918-1932), V.A. Grenning (1932-1964), A.R. Trist

(1964-1970), C. Haley (1970-1974), W. Bryan (1974-1981), J.A.J. Smart

(1981-1985), J.J. Kelly (1985-1988), T. Ryan (1988-1993), N. Clough

(1993-1995), T.N. Johnston (1995-1996), G.J. Bacon (1996-1998), and R.G.

Beck (1998-).

ENVIRONMENTAL SYSTEM TO

WORLD STANDARD

Forestry in Queensland over the

last 100 years has been driven by a commitment to environmental best

practice.

The reason for this is simple, and was espoused by

forestry leaders of early last century: if your livelihood depends on the

forests, you look after them.

Last year was a milestone for DPI

Forestry, which, after an exhaustive independent certification process,

had its Environmental Management System certified to the International

Standard ISO 14001.

DPI Forestry's environment management is first

and foremost about sustainable forest management and

production.

Flow on benefits include assisting industry to

gain competitive market advantages and improved risk management.

FOREST

CONSERVATION STARTED IN THE 19TH CENTURY

by Peter

Holzworth

Archibald

McDowall

Richard M

Hyne

Many believe forest

conservation began in the 1970s with the burgeoning conservation movement,

but there were several men of conviction and influence in Queensland who

fought and won the battle for forest conservancy in the 19th

century.

Among them were Archibald McDowall, later to become the

state's Surveyor-General, and Richard Hyne, businessman and

politician.

The early history of the colony followed the usual

processes of new settlement - survival and establishment, expansion and

utilisation of natural resources and, finally, a growing awareness of the

need for protection and better management of those

resources.

During the early decades of settlement, the forests were

essential in supplying the new colony with timber for housing, mining,

fencing and the building of railways. The abundance of pine, red cedar and

other hardwood seemed limitless. But much was wasted due to

inaccessibility, transport problems, natural decay and the use of only the

best logs from the fallen trees.

Concerns about the indiscriminate

cutting of forests began to emerge in the 1860s and some timber

regulations were introduced by the government, but these only provided low

level controls on timber-getters. In any case, the government was

committed to settlement and introduced Acts of Parliament in 1860 and 1868

allowing the private purchase of land for agriculture and pastoralism.

This led to a greater reduction of the forests.

Among the

first voices to raise concern were those of the Acclimatisation Society of

Queensland. In 1870, the society wrote to the Colonial Secretary about the

over-cutting of forests, especially the effect such actions might have on

climate, but the government was unmoved.

In 1874, the

Secretary of State for the Colonies sent a questionnaire on forestry

matters to Walter Hill, head of the Brisbane Botanic Gardens. Hill

responded by pointing out the wastage associated with poor logging

practices and widespread ring-barking.

The case against these

practices was then taken up in 1875 by John Douglas, the parliamentary

member for the timber town of Maryborough who called for a select

committee to consider forest preservation, growth promotion and

conservation of forests for utilitarian purposes.

In that

year, a Select Committee on Forest Conservancy deliberated on a number of

these issues. It accepted evidence from many sources, including two

Maryborough men, William Pettigrew and Robert Hart, both of

whom had sawmilling interests. The committee made seven recommendations,

but the government took little notice of most of them.

Argument and

debate on forestry matters continued throughout the 1870s, but the timber

industry had little political clout compared with that of the pastoral

lobbyists.

Enter Archibald McDowall. McDowall spent his early

professional years (the 1860s) surveying in the Maranoa, Warrego and

Kennedy districts, but it was during his time in the Maryborough-Wide Bay

area that he made his presence felt in the debate over the best use of the

state's forests.

And he did it in practical ways. While others had

advocated logging restrictions, the introduction of forestry legislation

and the increased reservation of productive forestry lands, McDowall -

while in agreement with these sentiments - went a step further in

promoting trial plantings, silvicultural practices in forests and many

other forestry innovations.

McDowall carried out plantation

experiments on Fraser Island from 1875 to 1885. His men cleared

undergrowth around kauri pine seedlings and saplings to encourage greater

growth. They also extended logging clearings in the scrub, planted them

with kauri seedlings at set spacings and cleared narrow laneways through

the scrub and planted them with seedlings as well.

In

addition to the experimental plantings, he prohibited licences to cut pine

on the island in order to retain mature seed trees for future generations.

He also introduced tree-marking and sale of logs at stump, both modern

forestry practices. All this by 1889!

If Archibald McDowall saw

forest conservancy largely from a forest guardianship and arboricultural

perspective, Richard Matthews Hyne saw it as a necessary bulwark against

declining resource availability for the timber industry in

Queensland.

Hyne, from Maryborough, was deeply involved in local

politics, his region's burgeoning timber industry and forest conservancy

generally. He was not a government officer like McDowall but a successful

businessman engaged in timber-getting. He also was the Member for

Maryborough.

In 1889, Hyne introduced a successful motion in

parliament that the government act on forest replanting and create a

Department of Forestry. Although Hyne's motion was carried, no action

ensued immediately. This was not the first mention of a forest overseeing

body, as a select committee had recommended the call for a Forest

Conservancy Board 14 years before - in 1875.

In 1890, the

Queensland Government called for reports on forestry

matters.

Commissioners who made recommendations on these reports

included P. McLean, Under-Secretary for Agriculture; P. MacMahon, Curator

of the Botanic Gardens; A. McDowall, Inspector of Surveys and former

District Surveyor at Maryborough; and L. G. Board, Land Commissioner at

Gympie and Maryborough.

The commissioners recommended a plan for

forest management, emphasising three aspects:

* Conservancy -

reservation and management of existing forests

* Regeneration -

replanting and enriching production forests, and

* Extension -

extending forests into treeless areas

A Forestry Branch was created

in 1900 within the Department of Public Lands and Inspector of Forests

Leonard Board was appointed.

From a forestry viewpoint this was a

fitting conclusion to the 19th century and to the beginning of

government-approved forest conservancy.

A

FORESTRY SNAPSHOT

![Forest Showroom, George Street, Brisbane 1939]()

The Queensland

Government Forest Showroom in George Street, Brisbane, in 1939

Although

most public relations of this type is now done by industry, DPI Forestry

continues to promote timber as "the most environmentally-friendly building

product"

The forest industry is one of the

top 10 contributors to Queensland's economy and ranks as the state's

seventh largest manufacturing sector.

Industry segments

include forest growing, log sawmilling, re-sawn and dressed timber

processing, preservative treatment of timber, joinery and furniture

manufacturing, paper and paperboard production, and reconstituted board

manufacturing.

The industry is one of the main sources of

employment in many regional centres and consists of around 400 sawmills

and associated processing facilities that provide employment for more than

17,000 people. In economic terms, for every dollar spent on the raw timber

resource, a further $11.30 is injected into Queensland's

economy.

For every 10 jobs created directly by the industry, a

further 8.5 jobs are created in the wider community. In direct terms, the

annual value of the industry is estimated at $1.7 billion, however, when

flow-on impacts are considered, this value rises to $3.3

billion.

(Source: Centre for Agricultural Economics, 1998.)

VISIONARY CHANGES FORESTRY

FOREVER

Forestry's

visionary: Edward Harold Fulcher Swain

The turning point for forestry in

Australia has often been seen as one man, a rumbustious larger-than-life

forest visionary, Edward Harold Fulcher Swain.

A New South Welshman

by birth, Swain was made Director of Forests in Queensland in 1918 and

served in that position until his dismissal in 1932.

At the time of

Leonard Board's appointment as Queensland first Inspector of Forests in

1900, Swain already had a year under his belt with the Forestry Branch NSW

Lands Department.

He spent 16 years in NSW before heading to the

United States on a two-year self-funded trip to study American

forestry.

Swain returned to take up the position of Forest

Inspector at Gympie in 1916 and became the first senior forester to

seriously question the use of European forest principles in

Australia.

Appointed Queensland Director of Forests in 1918, Swain

began his 14-year crusade to revolutionise as much of forestry as he

could.

He dictated the curriculum for the study of forestry

in Queensland, writing silvicultural manuals based on Australia's climate

rather than that of Europe's.

He set up Queensland's first forest

nurseries.

He established some of Queensland's first plantations,

including the lofty giants now surrounding the Glasshouse

Mountains.

He saw forestry as a business to be managed on business

principles.

He garnered enough support to set up the Queensland

Forest Service as a department in its own right and then moved towards

possibly his most memorable achievement - preventing the erasure of the

magnificent hoop pine forests in the Mary and Brisbane valleys.

The

pro-development Lands Department of the day was determined to clear these

forests for the growing dairy industry, but Swain locked horned with the

department's officialdom and won.

Swain was a brilliant thinker who

did remarkable things for the conservation and management of forests in

Queensland, but he worked with little fear or favour towards his political

masters.

This attitude saw him at loggerheads with any number of

elected and non-elected officials, and eventually proved his

undoing.

When the State Government of the early 1930s wanted to

open the hardwood forests of north Queensland for settlement, Swain played

the role of conservationist and vehemently opposed the plan.

He

claimed a Royal Commission for the Development of North Queensland was

"rigged", and wrote a dissenting 200-page Royal Commission report

himself.

Although his views were later endorsed by the

Auditor-General and finally adopted by the government, Swain's political

masters thought he had gone too far, and dismissed him, without

compensation, four years before his contract was to expire.

Swain

left Queensland to become NSW Commission of Forests for 13 years, and

completed his career as a United Nations forestry consultant in Ethiopia

until 1955.

E.H.F. Swain spent his retirement years in Queensland,

the state he loved best, and died in 1970.

MOTOR VEHICLES

MAKE EASY ACCESS TO NATURAL AREAS

Few things have increased

recreational visits to Queensland's forests over the past 100 years as

much as the development of the motor car.

And, according to the

Department of Natural Resources, more people camp in natural areas each

year than attend the home games of the Bronco's, Bullets, Brisbane Lions

and Queensland Reds combined.

A recent DNR study confirms

Queenslanders' attraction to natural landscapes, finding that 25 per cent

of the south-east Queensland population over 15 years camp at least once a

year.

The study also shows that 51 per cent of the south-east

Queensland population pleasure drive in state

forests.

Traditional family vehicles are the most frequent

visitors. These make up around one-third of vehicles traversing our

forests. Four wheel drives make up just one-fifth of the

visitors.

The Department of Natural Resources manages state

forests to cater for the myriad of nature-based recreational activities

that visitors enjoy

DNR Permits Officer Donna McCarther said most

people who applied for a "permit to traverse" a state forest usually

wanted somewhere to go to get away from the hustle and bustle of their

daily lives.

Permits are also required for nature-based cycling,

horse riding, motorcycle riding and camping in most state forests in

Queensland and can be obtained through regional DNR

offices.

However, access to most day use areas, walking tracks and

trails, and designated forest drives, does not require permits.

NATIONAL PARKS GREW FROM

BUSH EXPLORATION

This family enjoyed

a bushwalk at Coomera Gorge, in the Lamington National Park, in

1938

As well as recognising the 100th

anniversary of the establishment of a Forestry Branch in Queensland, the

National Parks Association of Queensland (the NPAQ) is celebrating the

70th anniversary of its establishment in 1930, under inaugural president,

Mr Romeo W. Lahey.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there

were a number of keen adventurers, bushwalkers and bird watchers exploring

the mountains and scenery of south-east Queensland. Roads were little more

than tracks and transport was by foot, train, milk and cattle trucks and,

occasionally, private vehicles.

Through these activities, it was

realised there was a necessity to preserve virgin areas of scenic beauty

in their natural state for the enjoyment of future

generations.

As a result, legislation to establish national

parks in Queensland was enacted in the early 1900s and the first national

park was proclaimed on 28 March 1908 at Witches Falls, Mt

Tamborine.

By 1930 the number of parks grew to 16 and, by 1940,

investigations and submissions resulted in a further 123 terrestrial and

marine national parks being proclaimed, due largely to a close association

between the Queensland Forest Service and the fledgling NPAQ.

Not

until later was the concept of preserving species and biodiversity

understood and accepted. The need to retain species of flora and fauna and

be aware of the surrounding environment is even more urgent

today.

This has required the NPAQ to exercise a greater degree of

vigilance in

monitoring both Commonwealth and state legislation to

ensure it retains and protects world heritage areas and Australia's

national identity.

QUEENSLAND CELEBRATES

100 YEARS OF FORESTRY

Executive Director, DPI

Forestry, Ron Beck

Queensland celebrates 100 years

of forestry this year. In what was one of the earliest formal recognitions

of the need for forest management, the Queensland Government established a

Forestry Branch in its Department of Public Lands in 1900.

Mr

George Leonard Board, the then Land Commissioner for the Gympie,

Maryborough, Bundaberg and Gladstone Districts, was appointed the state's

first Inspector of Forests.

Known to all as Leonard Board, he took

up his position on 1 August 1900.

In 2000 the Queensland Government

agencies now managing forests in Queensland have planned a number of

celebrations to commemorate Queensland's forest

centenary.

Community organisations have also joined the

celebrations. These events include public displays and community

activities in Brisbane and throughout Queensland.

Present-day DPI

Forestry Executive Director Ron Beck said the range and nature of state

government forestry functions had continued to evolve and develop and

today were managed by DPI Forestry, the Department of Natural Resources,

the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Department of State

Development.

"These agencies, together with the timber industry,

forest industry workers and the broader community have been key players in

the developing relationship between government, industry and the community

during the past 100 years.

"This 100th anniversary provides

Queensland with an avenue by which we can pay tribute to the early

architects of the forest and timber industry and those who have progressed

the profession down the years.

"Their vision, enthusiasm,

innovation and downright hard work created a multi-million dollar industry

which is essential to the health of the Queensland economy," Mr Beck

said.

Mr Beck said it was his privilege to head DPI Forestry

as it entered the next 100 years.

"It will be difficult to fill the

shoes of our pioneering giants, but they have shown us what can be

achieved through commitment and a sense of purpose," he said.

SERVICE CELEBRATES 25

YEARS

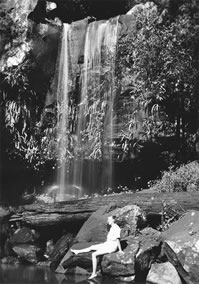

A young

bushwalker enjoys Curtis Falls in Tamborine National Park in

1937

As well as 100 years of forestry,

this year marks the 25th anniversary of the Queensland Parks and Wildlife

Service. The Service was formed on 5 June 1975 under the National

Parks and Wildlife Act.

It combined the National Parks Branch of

the then Department of Forestry and the Fauna Conservation Branch of the

Department of Primary Industries and created a single government authority

responsible for conserving native plants and animals and areas of scenic,

historic and scientific interest.

The Service's lineage,

however, can be traced to the 19th century.

In 1878 Tamrookum pastoralists

Robert Martin Collins and his

brother William visited the United States Robert and were

impressed by the world's first national park, Yellowstone National Park,

created in 1872.

As a member of Queensland Parliament (from

1896 to 1899) and Queensland President of the Australian Royal

Geographical Society, Robert Collins campaigned to

reserve scenic areas of the McPherson Ranges he could see from his

home.

His lobbying proved successful and the government accepted

the national park concept, passing the State Forests and National Parks

Act in 1906.

The early 1900s also saw local councillors Syd Curtis

and Joseph Delpratt became alarmed at the amount of clearing taking place

on Tamborine Mountain.

On 15 June 1907 the council

recommended that a part of the mountain be set apart as a reserve and on

28 March 1908 Witches Falls National Park became Queensland's first

national park.

Later the same year a halt was declared in clearing

the dense forests along the top of the Bunya Mountains when Bunya

Mountains National Park was declared.

On 31 July 1915 an area of

47,000 acres (19,000 ha) in the McPherson Ranges was reserved as Lamington

National Park, thanks to Collins' foresight and

the efforts of a young engineer Romeo Watkins Lahey, from a Canungra

sawmilling family.

Lahey convinced the Lands Minister that a large

reservation in the rugged area would have more benefits to the community

than logging and clearing and spread the national park concept more widely

when he became the founding president of the National Parks Association of

Queensland in 1930.

Over the years, the Forestry Department had a

small but very dedicated staff working on national parks. A handful of

rangers was responsible for managing and protecting parks often many miles

apart and they struggled to do their job effectively.

Fortunately,

foresters always had an eye out for the best of nature and landscape and

identified and recommended scores of areas large and small to be added to

the slowly growing Queensland national park tenure.

Today's

Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service is responsible for managing 212

national parks covering 6,623,648 ha or about 3.8 percent of Queensland.

THE

EVERGREEN YEARS - MILESTONES IN QUEENSLAND'S FOREST

HISTORY

by Peter Holzworth,

Ian Hatcher, and Kieran Lewis

William Pettigrew,

who set up Queensland's first modern sawmill on the banks of the Brisbane

River in 1852

Tins of tubed hoop

pine seedlings ready for transporting to Queensland's first major native

conifer plantations

Log punting

at McKenzie's Jetty on Fraser Island in 1929. Fraser Island was the site

of early exotic pine plantations in Queensland

A steam tractor hauls

sawn hoop pine from a Benarkin sawmill, c. 1923

![Steam logs for veneer production]()

Steaming logs for veneer

production at Brisbane Sawmills in 1932.

There were 600 licensed

sawmills in Queensland in the 1930s. (There are about 400

today)

In 1823, Surveyor-General John

Oxley sailed into the Brisbane River and saw "timber...of great

abundance". Just 17 years later, following a time as a penal depot, free

settlers began to colonise areas to the north and west of

Brisbane.

Much timber was needed in the colony for housing,

boat-building, fencing, and other development and forests were logged for

pine, cedar and other hardwoods.

William Pettigrew contributed to

the production of sawn timber for the burgeoning colony by opening the

first sawmill in Brisbane in 1852 and his name has become synonymous with

the start of a genuine forest and timber industry in

Queensland.

The Queensland Government proclaimed its first timber

regulations in 1860 with the accompanying threat of seizure of logs if

timber-getters were found not to be complying with the regulations. The

first timber reserves were gazetted in 1870.

Archibald

McDowall became a strong advocate of forest conservancy around this time.

A district surveyor at Maryborough and later Surveyor-General of

Queensland, McDowall showed great vision on many forestry issues,

foreshadowing later forest management practices and the drive for forested

land reservation.

A Forestry Branch was created in 1900 in

the Department of Public Lands and an Inspector of Forests, George Leonard

Board, was appointed, along with two forest rangers in supporting field

roles.

At the time of Board's appointment, the area of forest

reservation in Queensland was about a million and a half acres. Within two

years, this had doubled and, by the end of 1904, the figure had risen to

well over three and a half million acres.

The extent of the forest

estate was rapidly increasing but exploitation of Queensland's forests for

timber continued.

A further positive move in the first decade of

this century was the enactment of the State Forests and National Parks Act

of 1906. Effective from 1907, Crown lands for the first time could be

reserved as state forests or national parks.

In 1908

Queensland's first national parks were declared at the Bunya Mountains and

Mt Tamborine.

In 1911, under new Director of Forests N. W.

Jolly, the need for a "determination of annual permissible cut" was

proclaimed. This was formalised in 1926 when the Forestry Branch regulated

the amount of timber that could be cut by the industry in state forests

and timber reserves.

During the tenure of Jolly, from 1911 to 1918,

forestry began to take on a professional image for the first time. The

seeds of a new "Forestry" were being sown - forest inventory surveys,

yield calculation, silvicultural research trials, timber technology and

rudimentary fire protection.

The early exploitation of the

forests had diminished the "great abundance" of Oxley's day, but forest

management changes about to be made by modern foresters and rangers were

to redress the imbalance.

Strict rules covering the logging

of hardwood forests were introduced in 1937, based on sound silvicultural

principles and with the goal of maintaining sustainable harvesting of the

hardwood needed to meet the growing demand of the construction

industry.

The plywood industry began during the First World War. By

1926, there were eight plywood plants in the state, using six million

super feet of timber, mostly hoop pine. The Sawmill Licensing Act was

passed in 1936 regulating the sawmilling industry when there were 600

sawmills registered in the state.

During the Depression of the

early 1930s, various relief programs were provided to save people from the

dole. During World War II, massive quantities of timber were cut for the

war effort and the industry was declared an essential industry.

The

beginning of Queensland's enormously successful native conifer planting

program began in the 1920s. The early plantations were of native species

such as hoop pine, which required very fertile sites also in demand for

agriculture and settlement.

Those first plantations were seeded by

the newly-named Queensland Forest Service in 1920-21 and were mostly hoop

and bunya pine. The Mary Valley, the Brisbane Valley and far north

Queensland were destined to become the principal centres for growing these

conifers.

Ten years after the native conifer plantation program

began, the Queensland Forest Service began its exotic pine program. Early

plantings of pinus species occurred at Fraser Island, Atherton and

Imbil.

Forest conservators N.W. Jolly and E.H.F. Swain played

pivotal roles in the development of these

plantations.

Swain's use of matching species around the

world, using similar climatic patterns, was very successful in identifying

slash (Pinus elliottii) and loblolly (Pinus taeda) pines as being suitable

for Queensland.

Caribbean pine (Pinus caribaea) would show

great promise in trials in the mid-1970s, becoming successful north of

Beerburrum.

From 1945, various Queensland governments actively

supported a freeholding policy that allowed private citizens to purchase

and clear large tracts of Crown land for agricultural

production.

The Forestry Department, as it had then become,

challenged many freehold applications and was successful in retaining vast

areas, some tens of thousands of hectares, for state forests.

But

it was a fundamental legislative change that occurred in 1959, the

promulgation of the Forestry Act, which has been the driving force behind

forest management in modern times.

Among other things, the Forestry

Act enshrined cardinal principles of forest management including the

permanent reservation of forests, the perpetual production of timber and

associated products, and the necessity for soil and environment

conservation and water quality protection.

For some, however,

these safeguards were not enough, with sections of the community seeing

forests as having values and uses beyond timber production. This came to

head in the battle over management of the wet tropics of north Queensland

in the 1980s and 1990s.

Struggles for stewardship of the

forest estate became militant, vociferous and widespread, leading to other

confrontations at Fraser Island and in the Conondale Ranges.

The

Regional Forest Agreement negotiations of the late 1990s, however, brought

a return of balanced decision-making based more on science and knowledge

than rhetoric and emotion. Queensland's forest stakeholder agreement,

covering native forests in south-east Queensland, is widely accepted as a

productive model for the future of the forest and timber

industry.

Other important dates for modern forestry in Queensland

included 1975, when an entire section of the Forestry Department became

the Queensland National Parks and Wildlife Service (which this year

celebrates its 25th year), and 1996, with the formation of the Department

of Natural Resources, which now has regulatory control of Queensland's

forests.

WOMEN OF THE WOODS

The four Lynch sisters, Mary,

Kate, Nell and Rose, toil in forests near Gympie in the late

1800s

(John Oxley Library photograph)

An early colonial home - forestry womenfolk provided

for their families in primitive conditions

No story about forestry in

Queensland would be complete without mention of the essential role played

by women down the years.

Settlers who forged their way through deep

timber often did so with their families in tow.

It was the

women, often just young girls, who raised and educated children, provided

for the family, worked at making a home out of a slab hut with dirt

floors, and gave essential medical aid, all with virtually no money or

home comforts, and miles from the nearest settlements.

But home

duties were not the only contribution of the women of the woods. Many

worked as hard cutting timber as the males in their families.

An

example of the indefatigable spirit of these early women is the four Lynch

sisters, Mary, Kate, Nell and Rose, who were daughters of Irish immigrant

Cornelius Lynch.

Cornelius set up a cattle property near Gympie in

the late 1800s and, being a timber-cutter, taught his daughters to clear

and fell pine and hardwood mill logs, drive bullock teams, carry out

contract fencing and cart wood for the Gympie mines.

The women

worked hard and were much in demand for they were sober, industrious and

stood no nonsense. One stranger who made an unseemly remark found himself

dragged from his horse and thoroughly rolled in a mudhole.

They

were proud, too, in the way of the Irish. A neighbour once noticed them

working hatless and bought hats for each of the girls. Next time he drove

by he saw the hats nailed to a fence post. They would take no

charity.

The girls made a good living cutting hoop pine in the

early 1900s and when timber became scarce near Gympie they moved to the

Nanango and Kingaroy districts. A bill of sale for this era shows 23,000

feet of timber sold for £6/14/5d (around $13.45).

The sisters

worked with their cross saws and axes in the Bunya Mountains and always

dressed in long black dresses when they were working.

What these

women did was not only hard physical labour demanding strength and

endurance, but it was conducted under primitive living conditions. They

were often the only women in the large logging camps and their

accommodation was a tent.

When opening up new areas, the sisters

firstly had to clear tracks so that the horse and bullock teams could get

to where the timber was cut.

The sisters were the subject of an

article in The Sunday Mail of 7 December 1975. Author Nev Hauritz quoted

two men who worked with the sisters, Charlie Birch and "Brigalow"

Masden.

Both men were around 80 years old then, but still had

vivid memories of the Lynches. They recalled "good looking women who were

a match for the male cutters".

But the four-sister felling team

disbanded when some of the girls married.

|